Thalidomide: The active substance and its consequences

Thalidomide is the active substance in the drug marketed worldwide under different brands including Contergan, Distaval and Softenon. It was developed in our laboratories in 1954. When taken during a specific period in pregnancy, the substance could cause deformities in unborn children. The children affected by this substance are known as the “Thalidomide babies”.

On this page, we provide an overview of the active substance. We explain exactly what Thalidomide is, how it was developed and how it acts in the body. We also address how the medicinal product can cause deformities and why this was not discovered earlier. We will also provide a short overview of how Thalidomide is being used today.

Content

The chemical composition of Thalidomide

What are Thalidomide's side effects?

Thalidomide can cause deformities in unborn children

How modern science explains the action of Thalidomid

The species-specific action of Thalidomide

Polyneuritis: Thalidomide can damage nerves

Was Thalidomide developed in Germany during the Nazi era?

The chemical composition of Thalidomide

Thalidomide is a derivative of glutamic acid. It is a crystalline solid, easily soluble in water, with the structural formula C13H10N2O4.

The chemical bond in Thalidomide is chiral. That means it can come in two forms known as enantiomers. As was later discovered, one of these enantiomers is teratogenic and causes deformities in embryos.Later research has shown, however, that the two forms (enantiomers) convert into each other in the body within a few hours. Even if only the non-teratogenic form is administered, both forms are present again in the body within a few hours. In other words, administering the non-teratogenic form cannot prevent the teratogenic effect of Thalidomide.

How does Thalidomide work?

The active substance Thalidomide has many properties. Some of these properties are positive: Thalidomide has a sedative and sleep-triggering effect, and it also has anti-inflammatory properties and inhibits the growth of certain cancer cells.

When inventing Thalidomide in the 1950s, our researchers at the time discovered that taking Thalidomide caused fatigue and sedation. They discovered that it was impossible to administer a lethal – and therefore fatal – dose. Since an overdose of all other sleep aids at that time could lead to death, Thalidomide was considered an important discovery.

How does Thalidomide trigger its sedative effect? Simply put, it appears to imitate one of the body's messengers that inhibits the transfer of information between nerve cells in the body. The brain, therefore, receives fewer signals. This has a relaxing and sleep-inducing effect on the body.1

Based on this effect, Thalidomide was used as the active substance in the medication Contergan and similar drugs worldwide. According to our information, the development and introduction of Contergan corresponded with the state of knowledge at that time and the applicable standards in the pharmaceutical industry.

Testing and use by children

Our information shows that studies were carried out on children before and after the market launch of Thalidomide. Among others, Thalidomide was given to children in the lung sanatorium in Wülfrath-Aprath and the Maria Grünewald sanatorium in Wittlich (Eifel). Unfortunately, such studies were quite common at the time.

We deeply regret having been involved in these drug trials as a company. The methods used to test medicines on children in the 1950s and 1960s are incomprehensible from today's perspective. They do not comply with the current strict ethical and legal rules for drug development and testing.

As the manufacturer, Grünenthal participated in the investigation into the use of Thalidomide at the Maria Grünewald sanatorium and supported the documentation in 2021.

What are Thalidomide’s side effects?

It was discovered that the substance Thalidomide could cause severe side effects, including deformities. Below, we provide more precise information about the side effects of Thalidomide.Thalidomide can cause deformities in unborn children

If Thalidomide is taken during pregnancy between the 34th and 50th day following the first day of the last menstrual cycle, it leads to deformities including:

- Complete absence or shortening of arms and legs.

- Deformities of the hands and feet.

- Deformities of the hips, digestive tract and genitals.

- Deformities or complete absence of the outer ear.

How modern science explains the action of Thalidomide

The mechanism of action of Thalidomide, and thus the explanation of why these deformities occurred, remained unknown for decades. The basis for clarifying the mechanism of action was presented by the working teams of Takumi Ito and Hideki Ando from the Tokyo Institute of Technology, as well as by Yamaguchi at the Tokyo Medical University, among others, in 2010.2 This knowledge was supplemented by various international research teams. New findings are being developed even today.3

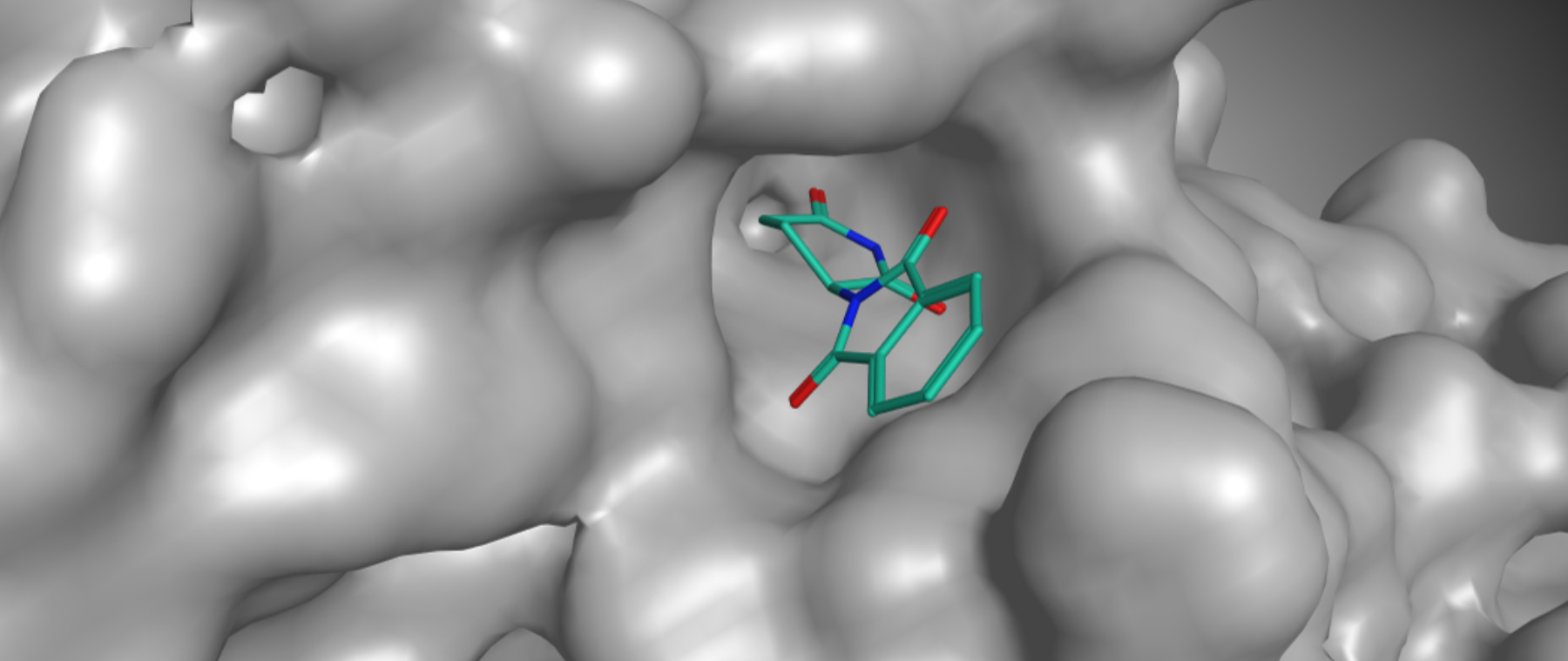

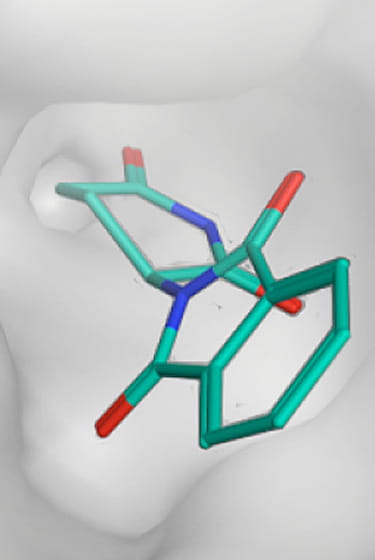

According to the current state of knowledge, Thalidomide causes deformities because, as a binding link, it bonds specific proteins in a child’s body that control, among other things, the formation of the extremities. This bond prevents a child’s body from being able to develop further.

Every cell in the human body contains proteins.4 They serve as molecular “tools” and can carry out various actions such as switching genes on and off, enabling cell movements, or acting as messengers.

Three types of proteins play a role in the mechanism of action of Thalidomide 5

- The protein cereblon can attract other proteins, almost like a magnet 6 These proteins are then “marked” by cereblon and broken down (destroyed)7

- The proteins Sall 4 and p63 are known as transcription factors. They can turn genes on and off like a switch. Sall 4 and p63 control growth, and the development of extremities and specific organs in a child's body.

The structures of cereblon and Sall 4 or p63 are so different that they do not fit together in their original states. They exist alongside each other. In this state, Sall 4 and p63 can stimulate the growth of extremities and control the formation of organs.

If Thalidomide is taken during a specific period in pregnancy, the active substance can reach the child’s body through the mother’s metabolism. Once it gets to this point, Thalidomide first docks to cereblon. At this point, a partially different novel structure is formed that can dock with Sall 4 and p63.

This video from the Dana Farber Cancer Institute explains the processes involved. However, the statement in the film that the medication was developed for morning sickness is inaccurate.

The species-specific action of Thalidomide

After Contergan was withdrawn from the market, researchers first attempted to prove the suspicion regarding the teratogenic effect in lab animals like rats, rabbits, and mice. These drug tests were typical at the time. The results were negative at first due to the species-specific action of Thalidomide. The substance does not affect all animals, just certain species. Teratogenic effects in pregnant animals could therefore only be observed in 1962 (after the withdrawal) when Thalidomide was specifically tested on a particular breed of rabbit, the White New Zealand Rabbit (NZW).

Polyneuritis: Thalidomide can damage nerves

Thalidomide can cause polyneuritis, an inflammatory disease of the nervous system, in people who use the drug. Symptoms include a sensation of numbness in the tips of the fingers and feet. It can also be very painful. In the case of longer-lasting complaints, polyneuritis also leads to a change in the nerve tissue that can be demonstrated by pathology.

Was Thalidomide developed during the Nazi era in Germany?

Grünenthal strongly condemns the atrocities of the Nazi regime and has repeatedly engaged in initiatives against the radical right. As is the case for many other companies, however, Grünenthal employed people in the post-war period who had previously held positions within the NSDAP [National Socialist German Workers' Party].

Some conspiracy theorists have concluded that Thalidomide was developed during the Nazi era by Nazi chemists and was tested on concentration camp prisoners as an antidote to chemical warfare agents. There is no reasonable evidence for these speculations.8 We examine two repeatedly expressed theories in greater detail below:

- There is a rumor that Thalidomide was developed before 1954, in the era of the Third Reich. Original documents (Lab report of Keller, Lab report of Kunz) and the witness testimony under oath of Grünenthal researchers Dr. Kunz and Dr. Keller in the Thalidomide trials9 prove, however, that the two scientists developed the active substance Thalidomide in the Grünenthal lab in 1954. The first patent was applied for in 1954.

- Even so, attempts are repeatedly made to create a link between the development of the active substance Thalidomide and the Nazi past of Dr. Otto Ambros, later a member of the Advisory Board. However, Dr. Ambros was never an employee of the Grünenthal company. He joined the Grünenthal Advisory Board in 1972, eleven years after Contergan was withdrawn from the market.

In a research report that appeared in 2016, historian Dr. Niklas Lenhard-Schramm investigated a possible connection between Thalidomide and the Third Reich, as well as the plausibility of the theories presented. He concluded that the conspiracy theory allegations that Thalidomide had already been developed before 1954 lacked credible evidence.10

Was Thalidomide also sold in countries other than Germany?

After Contergan was put on the market in Germany in 1957, licensees and distribution partners gradually distributed Thalidomide-containing medications in many countries worldwide. The products were available on the market under different brand names, such as Distaval and Softenon.

In some countries like Brazil, Italy, and Spain, companies distributed medications containing the active substance of Thalidomide without the participation or authorization of Grünenthal.

In the United States, Thalidomide was not sold because the FDA was still evaluating its market approval when Dr. Widukind Lenz and Dr. William McBride discovered its teratogenic effects.

Grünenthal stopped sales of its Thalidomide-containing products in November 1961 and informed its distribution partners and licensees in the countries where they had distributed the medications.

Is Thalidomide still used today?

Research is still being conducted on Thalidomide. It was found that Thalidomide shows favorable properties in severe diseases, such as leprosy, bone marrow cancer and some autoimmune diseases.11,12,13 For example, in Brazil, Thalidomide is still used to treat leprosy, but with a special warning label that the medication cannot be used while pregnant. Recently, a young scientist was awarded the Eppendorf Young Investigator Award 2019 for detecting a new treatment strategy using the Thalidomide molecule – proving the chemistry behind Thalidomide can benefit further research as well.

Our company no longer produces any Thalidomide-containing products. Thalidomide is, however, relatively easy to create. Today, the manufacture of Thalidomide is no longer protected by the patents that Grünenthal held in several countries at the time. Grünenthal has no connection to third parties who offer Thalidomide-containing products. Of course, science, industry and regulatory authorities now know about the severe side effects Thalidomide can produce. The active substance’s manufacture and use are therefore subject to strict regulations. The product may be prescribed and dispensed only in accordance with a special program to prevent deformities in unborn children.14

Although Grünenthal does not manufacture Thalidomide-containing products anymore, we aim to collect and offer as much information about Thalidomide and its effects as possible through our Grünenthal Foundation. In this way, we will build a knowledge database over time. This knowledge is useful for Thalidomide survivors, and we also strive to make it available to patients with comparable concerns and needs. In addition, the Grünenthal Foundation aims to empower others to share their knowledge regarding Thalidomide and its effects.

More information about the Grünenthal Foundation can be found here and news about Grünenthal’s research can be found here.

1 https://www.netdoktor.de/medikamente/thalidomid/

2 Takumi Ito, Hideki Ando et al (2010): “Identification of a Primary Target of Thalidomide Teratogenicity”, in: Science (327 / 5971), pages1345-1350, available at https://science.sciencemag.org/content/327/5971/1345.

3Tomoko Asatsuma-Okumura, Hideki AndoNature et al (2019): “p63 is a cereblon substrate involved in Thalidomide teratogenicity”, in: Nature Chemical Biology (15), pages 1077–1084, available at https://www.nature.com/articles/s41589-019-0366-7.

4 A protein is a biological macromolecule that can contain several hundred amino acids, which are joined together by peptide bonds. Cereblon contains around 440 amino acids, for example.

5 The p63 proteins are ∆Np63α and TAp63α. The breakdown of the protein ∆Np63α causes damage to the extremities, while the breakdown of the protein TAp63α is responsible for damage to the ears. (Nature Chemical BIOLOGY | VOL 15 | NOVEMBER 2019 | 1077–1084

6 Cereblon acts as a substrate receptor within the E3-ubiquitin-ligase family.

7 Cereblon is part of the E3-ubiquitin family. Every E3-ubiquitin-ligase can mark certain proteins with ubiquitin, which signalises to the cells that these marked protein should be broken down or destroyed. This marks proteins that contain errors or that have changed. This mechanism manages the life cycle of proteins in this way.

8 Niklas Lenhard-Schramm (2016): „Die Haltung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen zu Contergan und den Folgen“, research paper from the WWU Münster for the Ministry for Health, Emancipation, Care and Ageing of the German State of North-Rhine Westphalia page 26f.

9 Dagmar and Karl-Heinz Wenzel (1968): „Bericht und Protokollauszüge vom 51.-100. Verhandlungstag“, in: Der Conterganprozess (II); Keller page 56ff, Kunz page 71ff.

10 Niklas Lenhard-Schramm (2016): „Die Haltung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen zu Contergan und den Folgen“, research paper for the WWU Münster for the Ministry for Health, Emancipation, Care and Ageing of the German State of North-Rhine Westphalia, page 26f.

11 https://www.emedicinehealth.com/drug-thalidomide/article_em.htm

12 David Millrine, Tadamitsu Kishimoto (2017): “A Brighter Side to Thalidomide: Its Potential Use in Immunological Disorders”, in: Trends in Molecular Medicine, (23 / 4), page 348 ff, available at https://www.cell.com/trends/molecular-medicine/pdf/S1471-4914(17)30025-4.pdf

13 https://www.netdoktor.de/medikamente/thalidomid

14 https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/thalidomide-celgenehttps://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/overview/thalidomide-celgene-epar-medicine-overview_de.pdf